I’ve been seeing lots of lists of summer reads lately, and

that reminded me of Goodbye, Columbus,

a book I associate with summer, because I read it during summer school.

I’ve been seeing lots of lists of summer reads lately, and

that reminded me of Goodbye, Columbus,

a book I associate with summer, because I read it during summer school.

My parents were very opposed to my sitting around all summer

long doing nothing. Since we had a big yard and a twenty-acre lake behind our

house, they weren’t interested in sending me to summer camp. So instead I went

to various summer programs offered by our school district.

The summer between my

sophomore and junior years in high school that meant taking the bus to

Pennsbury High for a summer course in literature.

I remember meeting in Room 222 – this was during the years

when that TV show, starring Michael Constantine and Karen Valentine – was on

TV. I can’t recall what else we read, but the book that stuck with me is Philip

Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus.

I was a voracious reader, but this was one of the first

books I read that was about somebody like me – Jewish, teenaged, growing up in

the suburbs. It was his first book,

published when he was 26, and included the title novella and five stories.

Wikipedia states that “Each story deals with the concerns of second and third-generation

assimilated American Jews as they leave the ethnic ghettos of their parents and

grandparents and go on to college, to white-collar professions, and to life in

the suburbs.”

Well, that was me right there – a second-generation American Jew.

My father even grew up in the same “ethnic ghetto” as Roth himself – the Weequahic

Park neighborhood of Newark, New Jersey.

I went on to read

more Roth, particularly Portnoy’s

Complaint, which informed my senior thesis, a book about Jewish

assimilation, among other things. I also got to take a course at the University

of Pennsylvania with Roth himself.

I went on to read

more Roth, particularly Portnoy’s

Complaint, which informed my senior thesis, a book about Jewish

assimilation, among other things. I also got to take a course at the University

of Pennsylvania with Roth himself.

It wasn’t a creative writing course, sadly;

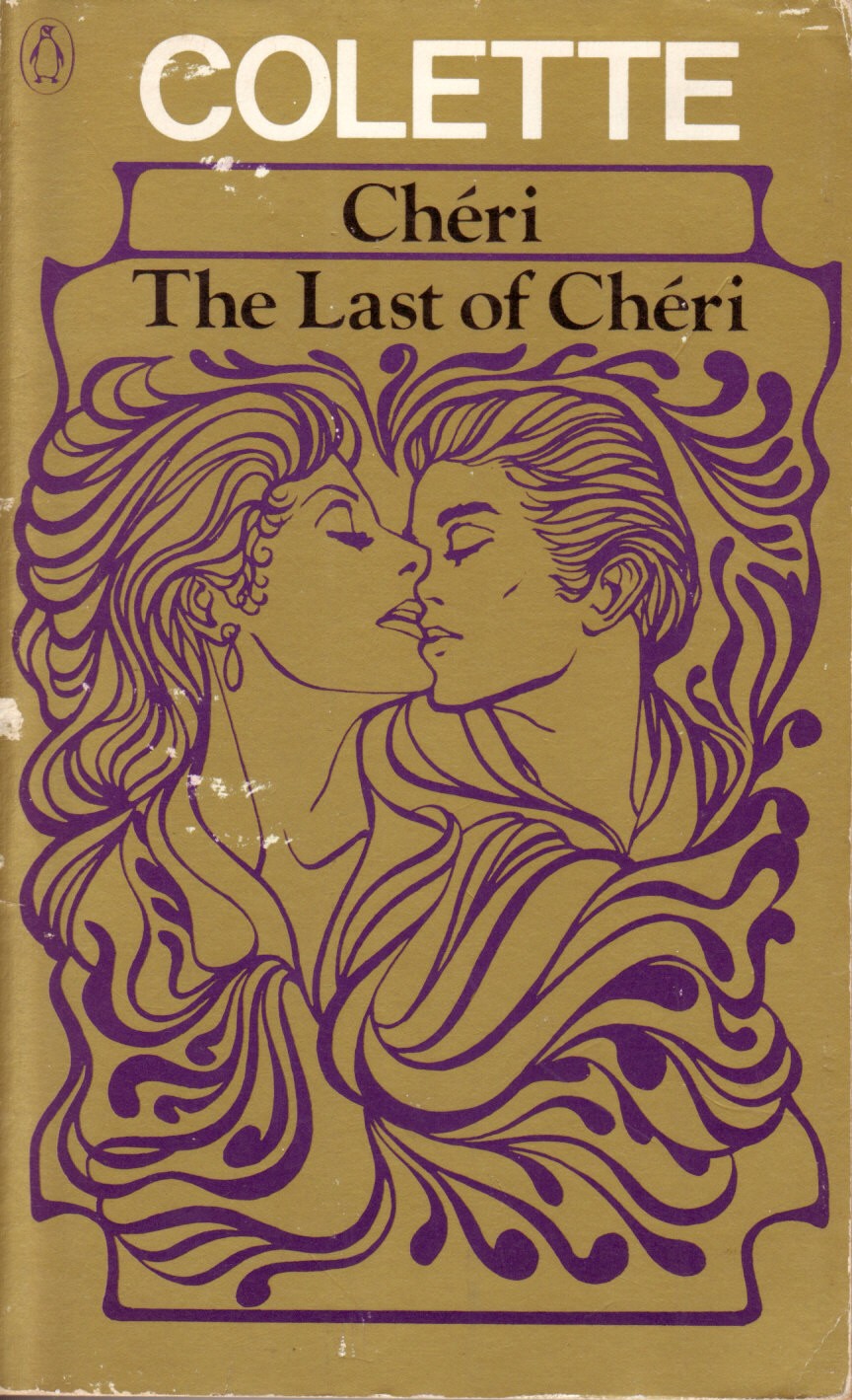

instead, we read a bunch of novels, including several by Colette, and then

wrote essays about them, which he critiqued heavily. I don’t think we ever

discussed his work in class – he just assumed, I guess, that if we’d signed up

for a course with him we knew what he’d written.

He was also kind

of a prick, a lot like the characters he wrote about, so maybe he just didn’t

care what we thought.